Biography: 2. Decca Years

/“In 1957, I started work at the Decca studios, as a sort of assistant office-boy and have been part of the record industry ever since as a recording engineer, record producer and record company executive.”

Kevin soon rose from “assistant office-boy” to Progress Chaser – this job involved co-ordinating the production elements of a new LP – finished master, cover photography and design, sleeve notes – and making sure the LP stayed on schedule. He stayed in this role until he got the opportunity he’d been craving – working on the sound side of the business. His first real job in the record industry was in the Duplicating Room. (He learned the skills which would serve him well in the years ahead – he would eventually come full circle and spend his last years in a room alone, transferring 78s onto reel-to-reel tapes, then expertly editing them to remove the clicks and scratches, the carpet eventually disappearing beneath the confetti of tiny sliced-out tape segments.)

KEVIN TAPE COPYING IN THE DECCA STUDIOS' DUPLICATING ROOM, EARLY 1960S

In May 1959, he became engaged to local girl Margaret Buss, who, appropriately perhaps, he met at Alf’s market stall; Alf would seek out cheap classical 78s for her. They married the following year, and moved from their local Kentish Town to Highbury, and it was there that their first son was born in 1961. At around the same time, Decca Studios in Broadhurst Gardens began to build their large Studio 3 at the back of the complex, off West Hampstead Mews. Decca bought up the leases of several adjacent properties, and in 1963, offered one of the flats to Kevin and his family. And so in June, the Dalys moved into 159 Broadhurst Gardens, almost right next door to the studios themselves.

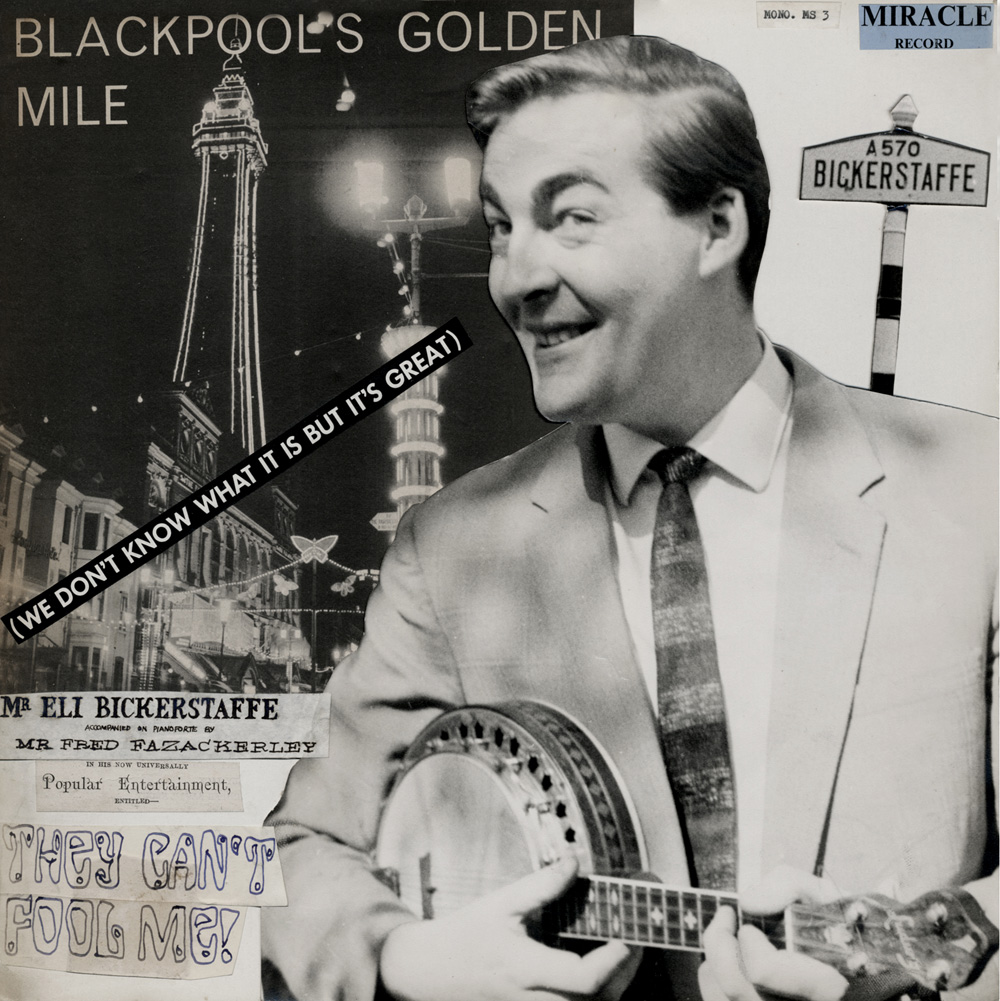

By this time, Kevin was in possession of his own fully-fledged George Formby-esque alter ego: Eli Bickerstaffe. ‘Eli’ was to make many an appearance on many Argo records over the years, and he even made two private albums of his own with various Decca partners-in-crime, including Michael Gough, Martin Smith, Mike Goldsmith, Harry Fisher, Chris Raeburn, Peter Attwood and Jack Clegg.

LP COVER FOR 'BLACKPOOL'S GOLDEN MILE' BY ELI BICKERSTAFFE: 'HE'S SO GOOD IT'S FRIGHTENING'

The third album, Blackpool’s Golden Mile (catalogue number MS 3 for those Bickerstaffe aficionados out there) boasted of Eli: ‘He’s so good it’s frightening.’ There are also a series of very funny photographs of Kevin and recording engineer Arthur Lilley dressed up in white tie and tails, playing the Decca grand pianos, and studio mixers, when no-one’s around; clearly it wasn’t all hard work then. Other pseudonyms followed: ‘Ciobhan O’Dalaigh’ often cropped up as a sleeve note writer, and once even created his own fictitious ceili band (see the Argo section).

Decca in those days was clearly a friendly, happy place to be, with a nice crowd of people. The inside of the studio building itself, once upon a time the Crystalate Studios, was often described as submarine-like: long corridors on different levels, large pipes along the walls; there were a myriad of doors opening onto editing rooms, transfer rooms, and of course, the three main studios themselves. The new Studio 3 was a long way from the front door – the whole length of the Decca submarine. Studio 1 was straight ahead as you entered the building, its control room high above the studio, accessible by a steep flight of stairs; Studio 2 was downstairs, and was the most intimate, and the most modern in feel. It was here that Kevin would record many of his albums as producer. Kevin was in the Decca studios when the Beatles had their audition (Decca notoriously turned them down), and knew Gus Dudgeon, then also working at West Hampstead as an engineer.

BROADHURST GARDENS IN 1963, WITH DECCA STUDIOS ON THE RIGHT

Meanwhile, 159 Broadhurst Gardens, which now had a new member of the family – Kevin and Margaret’s second son was born in September 1965 – was becoming an open house to colleagues and fellow engineers: Tony Hawkins, living in digs on his own would pop in every day for a cooked lunch, and have his ironing done by Margaret. On Friday lunchtimes, Alf Brightman would come for fish & chips, with perhaps producer Geoff Milne, disc-cutter Harry Fisher, or engineers Pete van Biene or Mike Goldsmith. It is important to stress the family nature of Decca at that time. As Kevin remembered:

"I would like to pay tribute to three people who to me symbolise the heart of the record business; hard-working and cheerful, ignoring with sage aplomb the chaos around them: Freddy Feltham, mechanical engineer who can and does make everything, from microphone stands to cutting heads; Charlie Glenister, wax-shaver, tape reclaimer and authority on the turf; and Dolly Milburn, who has soothed tired musicians with her nutritious beverages for a quarter of a century. There are hundreds of others, in every record company, and in many differing jobs; who hold the fabric of the industry together and make it possible for talent to be transfigured into black plastic."

KEVIN WITH ENGINEER ARTHUR LILLEY AND PRODUCER TONY D'AMATO IN DECCA'S STUDIO 3

Soon Kevin was working as an assistant engineer on Decca’s Phase 4 label, with the producer Tony D’Amato and engineer Arthur Lilley, on large classical recordings, with artists such as Leopold Stokowski and Carlos Paita. (When asked by D’Amato for a short orchestral run-through for sound levels, Stokowkski replied, “You know the work, I know the work, the orchestra knows the work – let us begin”, and promptly started; only Kevin and Lilley’s quick-wittedness saved the day.

KEVIN WITH COMPOSER SIR MICHAEL TIPPETT IN 1970

He also worked with Sir Michael Tippett, Sir Arthur Bliss and Jacques Loussier, and was starting to make a mark for himself as an ambitious and capable member of the Decca team; but his career was about to be pulled into a new direction.