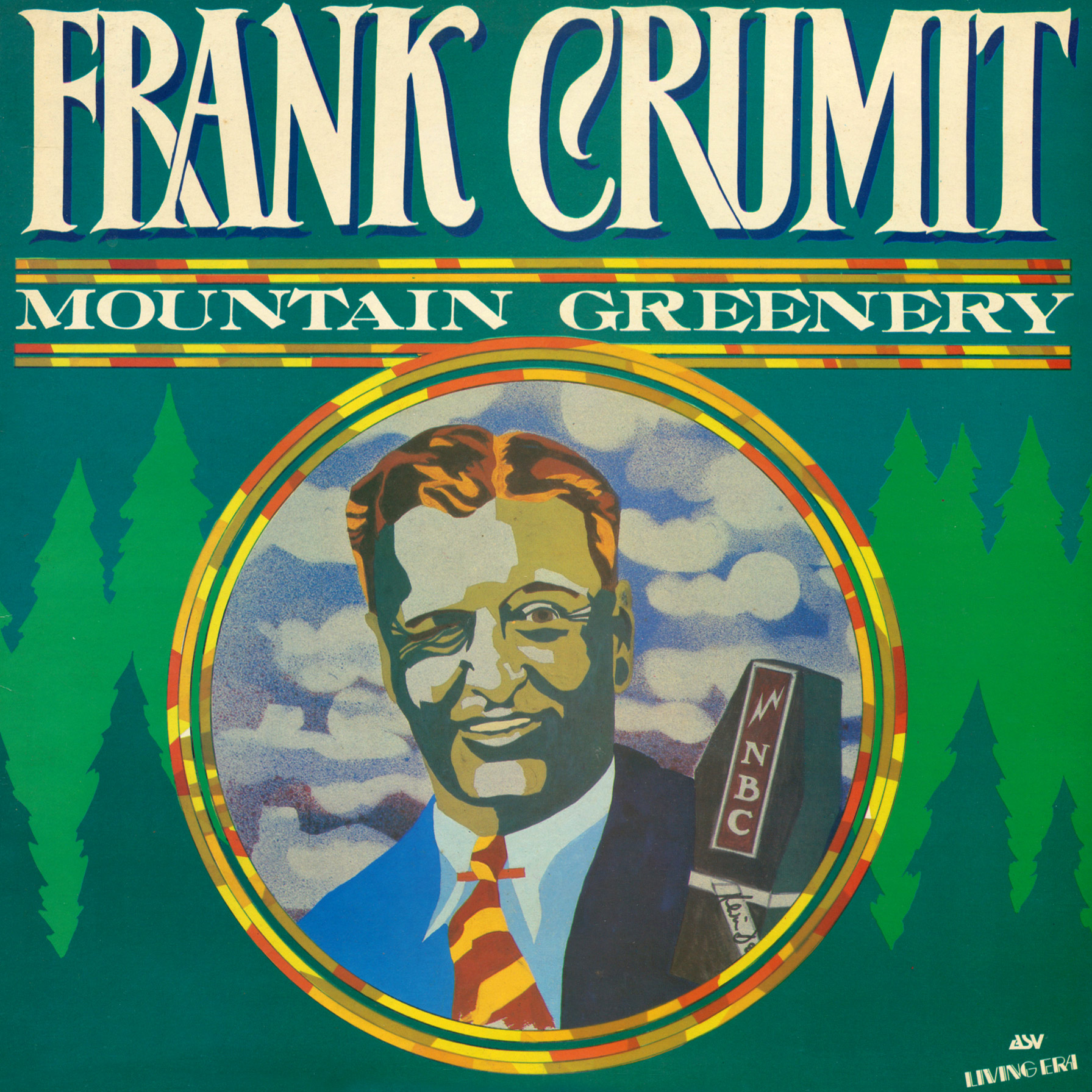

Frank Crumit - Mountain Greenery

/Frank Crumit - Mountain Greenery LP cover illustration by Kevin Daly

The Twenties are generally regarded as a decade of hedonistic escapism. The ‘war to end all wars’ patently had not; riot and revolution were sweeping Europe. In the United States, bright young things were forgetting their troubles by dancing until dawn to whichever dance craze was current that particular week, smoking reefers supplied by ‘Smokie Joe’ or drinking gallons of bathtub gin at speakeasies. Flappers’ skirts crept higher as their neck-lines plunged, and the dream of every true blooded young American was to be there when the twain finally met. It seems bizarre that concurrent with frenetic music, loose morals and bootleg liquor, one of the most popular recording artists should be Frank Crumit, a young man who sang tuneful, pleasing songs with witty and urbane lyrics, wry good humour and a keen sense of classy interpretation.

Frank Crumit was born on 26th September 1889 in Jackson, Ohio. His father was a moderately successful banker who sent his son off to the Culver Military Academy in Indiana, where Frank managed to matriculate as an engineer, despite spending half of his time on the sports field as an aggressive and dominating baseball and football player, and the other half as a leading light of the amateur dramatic and musical society. After graduating from college in 1910, he half-heartedly worked as an engineer for a couple of years, but gradually found work as a song and dance man on the Vaudeville stage. For several years he toured the seedier Vaudeville and burlesque circuits, writing songs in his dressing room and fitting them into shows whenever he had the opportunity.

He got his big break in 1918, when he was offered the juvenile lead in ‘Betty Be Good’. The success of this musical led to a booking for the ‘Greenwich Village Follies’ where he not only wrote and performed much of the show but also met his future wife, Julia Sanderson. She was already a leading subrette on Broadway and had appeared in many musical comedy successes when she met Frank Crumit in 1922. He wrote several songs for her new vehicle ‘Tangerine’ and appeared as a supporting actor in the production. They married during the run of the show and thereafter worked almost exclusively as a double act whenever possible.

In 1928, the Crumits branched out into radio. Although only six years old, the radio audiences were now measured in millions and the networks were wildly bidding against each other for established stars. Their first nationwide programme was ‘The Blackstone Cigar Show’ where they featured topical items blended with songs from their immense repertoire of comedy, musical and folk songs. By 1930, they had a vast continent-wide audience as a duo, and as a solo artist, Frank Crumit was in the recording studio almost every week and had by now written so many songs that he formed his own music publishing company to protect his interests.

Throughout the Thirties, their radio shows became the mainstay of the Crumits’ career. From their home in Springfield, Massachusetts, Frank and Julia travelled twice a day to the CBS studio to broadcast over the network. In the mornings they hosted a variety show and in the evenings they presented their long-running quiz ‘Battle of the Sexes’, which had CBS’s highest weekly listening figures. In 1935 Frank was delighted to be elected President of the Lambs Club, a society of fellow artistes engaged in charity work particularly in sports facilities for youngsters. Frank and Julia still made the occasional record, the last in 1941, recreating scenes from ‘Tangerine’. At the height of his radio fame, Frank Crumit died suddenly on 7th September 1943 at the early age of fifty-three. Julia Sanderson retired soon afterwards but survived him until 1979.

The recordings on this album were made between 1920 and 1929 and display Frank Crumit’s special talents as one of the world’s top record sellers. He was not only a success in the United States, but he had a large and devoted following in Britain and Australia. As a recording artist, Crumit was a major innovator; he was the first popular entertainer to record straight and sympathetic versions of traditional folk songs, and he had a direct influence on many later performers including talents as diverse as Burl Ives and George Formby.

Without any doubt, Frank Crumit’s most popular song was Abdul Abulbul Amir, written by the Irish composer Percy French in 1890, and set during the Crimean War. It is still one of the most requested items on BBC nostalgia shows, and it led to several follow-up versions where Abdul and his perennial adversary Ivan Skavinsky Skavar refought their battle in evermore complex fashion. The original 78rpm record was so popular that it was re-issued by public demand in 1953, twenty-five years after its first appearance.

During his childhood in Jackson, Frank Crumit heard many folk songs played and sung by the old-timers. In his version of The Bride’s Lament the very poignant lyric is set to a cheerful Irish dance. It makes for an incongruous combination, but it is classic Crumit. Billy Boy still survives in the English oral tradition and this American variant of the West Country song was first noted down in 1824. The wit is timeless and the same straightforward rustic good humour can be heard in Get Away Old Man, Get Away (more frequently heard these days in an alternative version ‘Maids When You’re Young’). Down In De Cane Break and Kingdom Coming And The Year Of Jubilo both had their roots in negro songs, albeit much re-written. Kingdom Coming was published in 1862 during the American Civil War and marks the high point of the career of Henry C. Work, second only to Stephen Foster as a chronicler of America’s young days. Work was strongly Abolitionist and the dry, sly humour of the lyric is written from the viewpoint of the southern slaves. The melody has become so well-known that it is frequently accepted as a genuine folk tune.

Many of Crumit’s own compositions are loosely based on folk idioms; Jack Is Every Inch A Sailor draws from the tradition of the Greenland whale fisheries, and The King Of Borneo, despite its South Sea setting, is basically Irish in treatment. This folk influence can still be felt in The Gay Caballero but by now Iberian Vaudeville influences are taking over. Jules Bussano’s Thanks for the Buggy Ride was written at a time when the model T Ford was to be seen taking over from horse-drawn vehicles in all the Ambridges of the Ozarks, and regrets the new high-speed transport.

The earliest recording on this album, Albert Von Tilzer’s Oh By Jingo, was featured in the ‘Greenwich Follies’ of 1920 and is a superb example of that never-never paradise island where the sun is always shining and the girls are always willing. It started a whole spate of similar material and another dreamy Honolulu lullaby written by Dick Whiting and full of subdued sexual symbolism is Ukulele Lady. The ukulele was the paramount machismo symbol of the Twenties: “can you play the uke?” read the advertisements, implying social and spiritual rejection if you couldn’t. Crazy Words, Crazy Tune graphically describes the drawbacks of living next door to such a would-be ‘Ukulele Ike.’ Frank Crumit himself was an adept ukulele player, and can be heard on several tracks accompanying himself in skilful fashion.

If anything, the Twenties encouraged lunacy on a grand scale. From Prohibition, probably the biggest lunacy of all, to pole-squatting, marathon dance championships and yo-yos. The popular songs reflected these obsessions with outlandish and generally tuneless numbers. The Song of the Prune comes from that particular strata of songs dedicated to fruit. (‘Yes! We Have No Bananas’ being the one that survived longest.) The song in fact has very clever and amusing lyrics and was one of Frank Crumit’s greatest successes.

In 1926, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers wrote their musical ‘The Girlfriend.’ The title song describing a lady who was ‘gentle, and mentally (nearly) complete’ became a classic, as did Mountain Greenery, written the previous year for ‘The Garrick Gaieties’ when Rodgers and Hart were still penniless beginners and only too delighted to submit free material to the junior members of Theatre Guild who were producing the show. Frank Crumit heard the song in rehearsal and was the first artist to record it. There are no tricks, no flambuoyance, just a sensitive and believable performance.

Frank Crumit’s repertoire included comedy songs, musical comedy hits, minstrel songs and ballads, all of which he recorded enthusiastically and definitively. He was not above appearing anonymously as the smooth, brilliantined crooner with Nat Shilkret’s band, (‘Just a Night for Meditation’ in this style can be heard on Living Era AJA 5002) or pitching in as compere of Minstrel Shows. In short, he was an adaptable, talented professional.

When told of Fats Waller’s death, Louis Armstrong remarked that he didn’t have to believe it if he didn’t want to. Similarly, Frank Crumit belongs to that collection of stars who are unique, original and timeless.

© 1981 KEVIN DALY